Where Is He Off To? The Japanese Businessman and Foreign Shadow in FEN

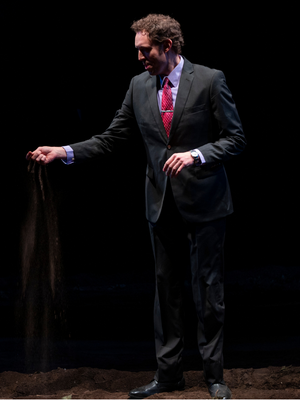

England, 1983. The premier production of Caryl Churchill’s Fen opened with British actress Cecily Hobbs greeting the audience, dispelling the haunting cries of a 19th-century human “scarecrow” who patrolled the stage before the house lights dimmed. Dressed in a contemporary man’s suit, Hobbs brought the audience back to the real world; nevertheless, she was not a native of the land, a ragged fenwoman, but a Japanese businessman holding a delicate camera1.

In broken English, this “Mr. Takai” of the “Tokyo Company” welcomed the audience to the Fens and delivered a blunt exposé of the land’s historical development and current market value. He introduced the 17th-century landlords who drained the Fens as “far thinking…brave investors” and the “wild people” living and laboring on the land as inferior brutes with “no vision.” Then, in an impressively long relative clause, he declared the present ownership of the Fens – his. The “Tokyo Company” was there to enjoy the “beautiful English countryside.”2

Off to find a teashop, Mr. Takai never returned to the story. In fact, it seemed like no character, neither the fenwomen nor the men, was aware of his presence as the ultimate possessor of their land, labor, and lives. Yet the specter of this dubious foreigner loomed as the churning machine of global capitalism – the very institution he personified and the play intended to subvert – strangled the humanity of the Fens. Through the Japanese Businessman, the originally western concept of capitalism was both confounded with global economic competition and crippled by the foreigner’s disjointed and accented English. Churchill’s appropriation of Asian identity was undeniably effective, except that this theatrical device operated at the unacknowledged expense of an obscured foreigner deemed threatening and suspicious. Hobbs’ physique as a British woman further disembodied and mystified the Japanese Businessman, rendering him a symbol of the all-pervading public and private constriction that enfolded the people of the Fens. Later in the play, this invisible spectator metamorphosed into the “Chinese radishes” and “Paki” buyers mentioned in an old farmer’s grumble, the same farmer who also speculated on Russians instigating working-class strikes after WWII and the French sending rockets to Argentina in the 1982 Falklands War, displaying equal parts of confusion, agitation, and rejection over these foreign subjects.3 While the ghosts of the 19th-century laborers roamed over the Fens in flesh-and-blood bodies, clutching at the living with a formidable force, the amorphous foreign forces in the play composed a vertiginous phantasmagoria of absurdity and menace, watching the English suffer in ambush.

The Japanese Businessman thus perched on the audience’s mind as an invisible spectator, stirring their anxiety over Asia’s rising power and the world’s changing order in the early 1980s. The proceeding post-war era from 1945 to 1979 was a precarious time for the U.K. to recalibrate its national identity and international relationship. India, Pakistan, Burma, and Ceylon gained independence from the British Empire soon after World War II. NATO bonded the nation to the United States against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Domestically, the state nationalized most industries, encouraged trade unions, and imposed high taxes to provide for a welfare state. Still, large-scale labor strikes broke out in the late 1970s. In the 1979 general election, Margaret Thatcher became the Prime Minister.4 The government was on the cusp of forsaking its previous market interventions, withdrawing from heavy industries, privatizing business, undermining unions, and regulating the increasing number of racial minorities that might “frighten” the nation.5 All the chaos would have eclipsed the peril of the agricultural Fenlands; nonetheless, the Japanese Businessman evaluating the history and struggle so particular to England instantly stamped the Fens onto the global landscape.

The microscopic community of the fenwomen was imbued with the general economic, political, and cultural anxiety of the time. 40 years later, Fen still pounds the hearts of audiences around the world as communities continue to experience the alienation, confusion, and suffocation caused by the lack of social mobility, economic stability, and emotional support. Yet the anti-Japanese sentiment might appear just as vivid for audiences in the United States. In the 1970s and 80s, while America’s heavy industry waned, unemployment rate surged, and national economy staggered (a situation similar to the U.K.), Japanese products swept over consumer electronics and automobile markets. Animosity seeped from the political and economic spheres to mass media and popular culture, leading to an intense wave of “Japan Bashing.” Along the “Buy American” campaigns, signs banning foreign cars were erected in parking lots, and imported vehicles from Honda, Toyota, and Nissan were vandalized.6 In 1987, a group of U.S. congressmen smashed Toshiba products on Capitol Hill.7 Such anti-Japanese violence spilled over to Asian Americans at large: in 1982, the year in which Fen was written, Vincent Chin, a Chinese American assumed to be Japanese, was beaten to death by two white men in Highland Park, Michigan.8 Japanese businessmen also became a particular trope of sinister and avaricious magnates, as seen in Michael Crichton’s murder mystery Rising Sun (1992), its film adaption (1993), and Tom Clancy’s techno-thriller novel Debt of Honor (1994).9

In the 1990s, Japan’s economic decline quelled the anger across the Pacific, and the “Japan Bashing” gradually dissipated as the U.S. galloped along its own economic growth. But the tension did not end: in recent decades, China’s increasing global presence has alarmed American politicians, businessmen, and the general public alike. The COVID pandemic has incited more flagrant anti-Asian hatred and violence. Meanwhile, the Asian American population has grown from 3.7 million in 1980 to 22.9 million in 2019, compounding the century-old metaphor of “yellow peril” that sees Asians as a threat to the security, prosperity, and health of the U.S.10

Now, once again on the stage of Fen, the Japanese Businessman gives his opening speech and vanishes into the 1100-square-mile farmland worth 2,000 pounds per acre in 1983.11 Where is he off to? The play leaves us no clue. Nevertheless, is it possible for us to overcome our suspicion? To face not only the systemic exploitation of the environment, labor, and womanhood on the Fens, but also our anxiety in an increasingly competitive and globalized world, to acknowledge the past and present shadow we have cast upon the foreign bodies? Perhaps then, the trace of the Japanese Businessman would be found.

Wenke (Coco) Huang is a recent graduate from Northwestern University, having majored in Performance Studies and Art History. Born and raised in Beijing, China, she is currently based in Chicago and working as a dramaturg, an independent researcher, a scenic/costume designer, and a puppeteer. She was the Assistant Director of The Island at Court Theatre, and will join the production of The Gospel at Colonus as the Production Dramaturg. Other credits include Villette at Lookingglass Theatre (Dramaturg), The Garden of the Phoenix for Lookingglass’ 50 Wards (Puppeteer), and The Seagull at Steppenwolf Theatre (Assistant Dramaturg).

Sources:

[1] Caryl Churchill, Churchill Plays : Two (London: Bloomsbury, 1990) 145-146.

[2] Churchill 147.

[3] Churchill 170.

[4] David Dutton, British Politics Since 1945: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of Consensus, 2nd ed.(London: Blackwell, 1997).

[5] Margaret Thatcher, interviewed by Gordon Burns, Granada TV. January 27, 1978.

[6] Brian Niiya, Japanese American History: an A-to-Z reference from 1868 to the present ( New York: Facts on File, 1993) 362.

[7] T.R. Reid, “Boycott Toshiba Computers, But Don’t Let Congress Force You,” Washington Post, July 13, 1987. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1987/07/13/boycott-toshiba-computers-but-dont-let-congress-force-you/a6130b8a-7be4-4737-8150-adc74e53443b/

[8] Niiya 117.

[9] Niiya 362.

[10] Abby Budiman, “Asian Americans Are the Fastest-Growing Racial or Ethnic Group in the U.S. Electorate,” Pew Research Center, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/07/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s-electorate/

[11] Churchill 147.