Sophocles the Poet: A Personal Essay

“Oh, Light of the sun,

Sophocles, Antigone

Oh most glorious light that ever shone

Upon Thebes of the Seven Gates, Across Dirce’s streams,

Oh eye of the golden sun,

Oh then did you shine

Upon the Man from Argos

With his Gleaming Armor.

Polyneices!

Running in unbridled fear now

In the harsh blaze of your dawn…”

“I am interested in Sophocles the poet,” Gabby whispered to me, inviting me into the interiority of her thoughts. The first time we met, we discussed the persistence of Antigone as a story whose resonance has not eroded over the years, decades, eons. As long as there is an oppressive force and a force of resistance rebelling against it, there is the story of Antigone. We relayed curiosities about Sophocles the scholar, the philosopher, and – ultimately – the poet, and it became clear to me that poetry was the entry point of this production.

I had been nurturing my own curiosity about the relationship between philosophy and poetry, two forms that Sophocles instinctively weaves in his work, for some time. Philosophy organizes thoughts into systems of thinking. Poetry refracts and organizes those emotions into systems of expression. I have always wondered about the journey of thoughts and emotions from the interiority of our being to the exteriority of our world, and the many expressive artistic modalities that are tools in that journey – which is to say, I’ve always been interested in hermeneutics, philosophies of interpretation. That’s the interesting thing about Antigone: there have been so many interpretations of this tragedy over the years, yet somehow the story never feels tired.

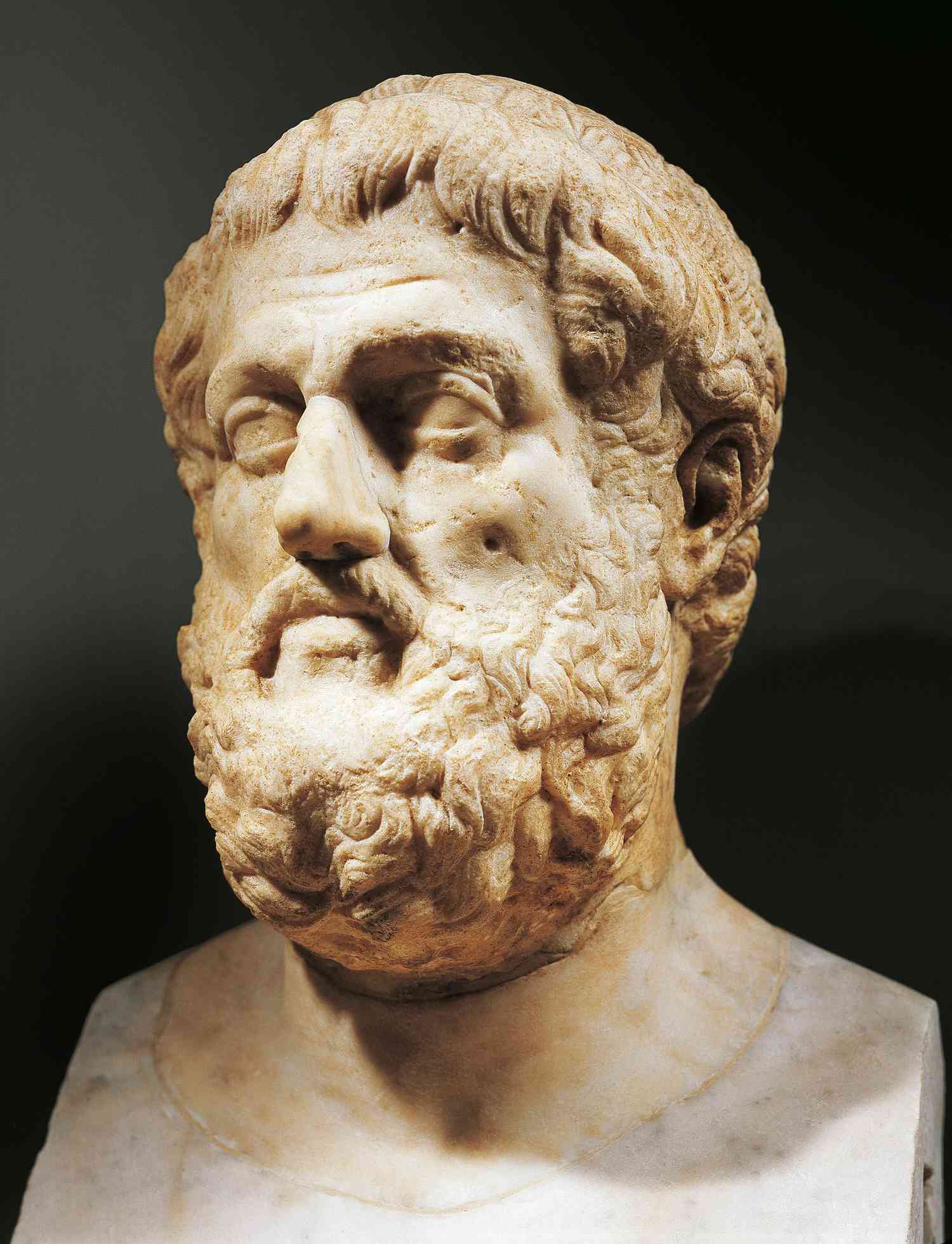

“At the end of the day, Sophocles was a poet creating in a time of war,” Gabby exclaimed at the apex of our musings. In his lifetime, Sophocles witnessed the triumph of the Greeks in both the Greco-Persian wars and the extensive Peloponnesian War, which stretched over two periods of combat separated by a six-year truce. As an audience to Sophocles’s poems and tragedies, we become witness to his thoughts as someone who was creating amid conflict. We see how his world permeates his writing, in what the characters of Antigone are fighting for and against. The Greeks called playwrights didaskoláï, which roughly translates to “teacher.” Artists were revered as educators and art was seen as educational source material. This idea that art is a reflection and refraction of the times has persisted throughout the centuries.

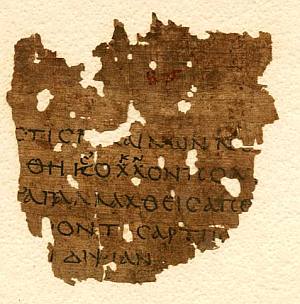

Greek drama and tragedy are deeply rooted in poetry – specifically lyric and epic poetry, poetic forms that began in Ancient Greece. Lyric poetry is usually a short non-narrative poem that expresses the speaker’s personal emotions and feelings. Historically, lyric poetry had musical qualities and was meant to be sung. Over the years, the umbrella of lyric poetry grew to encompass a broader category of non-narrative poetry, including sonnets, odes, and more. Epic poetry is a narrative poetic form that is often impressive in length and details extraordinary heroic adventures.

When we read Antigone through a poetic lens, it starts to sing. We can hear it as it leaves the page. We hear the rhythm and heartbeat, we hear the wails of grief, we hear the effusion of the elements – the weather of the world and the weather of the characters. What makes Antigone so special is the collision of the epic and the lyric. The existential and the personal. There is something that happens when we hear these bodies speak these words. The story doesn’t attempt to move us forward or bring us back. Antigone lifts us up, it activates us, it challenges us to transcend the theatrical space and become more deeply engaged citizens of the world.

Palestinian American poet Naomi Shihab Nye claims “We all think in poetry”, but I’ve had many conversations with friends who find poetry inaccessible (which I totally understand). There is a level of ambiguity you agree to when engaging with poetry or works informed by poetry, such as Antigone and other tragedies. From my understanding, poetry – like our emotions – is not necessarily concerned with or beholden to logic. Poetry challenges us to slow down, to listen actively and with our whole body.

To engage in poetry is to engage in presence, and like Antigone, to be present can be a radical act. Thank you for being present with us.