Falsettos Now and Then: An Aging Text Offers Perspectives on Growing Up

As a graduate student at the University of Chicago nearly fifteen years ago, I studied the American AIDS plays and how we think about their lifetimes as scholars, audiences, and artists. I wrote about how time and the practice of revival had made these texts into history plays that they were not originally written to be. They were written as urgent portrayals of their moment, but time had infused them with a dramatic irony they hadn’t been built with. In essence, “now” receded into “then,” and newer audiences brought with them newer information—they knew more than the characters did about what was going to happen.

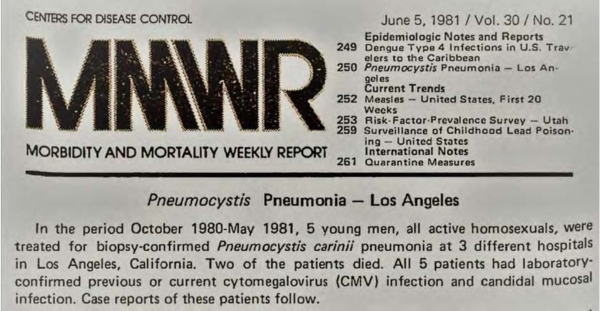

The lifetimes of these texts have created a knowledge gap between their characters and their audiences. Falsettos depicts some of the earliest days of the AIDS epidemic seen in an American theatrical text; for a show that takes place in 1981, that gap is the widest of all. In June of that year, the CDC issued a report that was the first official documentation of what would later be known as AIDS. Whizzer would’ve been one of its earliest victims. In 1981, concrete information was scarce. The term “AIDS” would not be used for the first time until 1982. The virus that causes it was discovered in 1983. With texts that take place later in the epidemic, modern audiences know more about what will unfold as it drags on. In this case, they possess the details of what it would be—or that it would be at all. Act One of Falsettos began as a one-act called March of the Falsettos, written, set, and first performed before AIDS was on anyone’s radar.

When the full text of Falsettos premiered almost ten years later, the presence of AIDS informed how audiences watched Act One in a way it could not have when March of the Falsettos stood on its own—the impending epidemic became a dark undercurrent that the characters know nothing about. For audiences, Falsettos is a show about AIDS, an epidemic that would extend far beyond the bounds of both the story and its original production; for the characters, the term “AIDS” does not exist as they navigate an illness first known as gay cancer, gay plague, or GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency).

In many ways, Falsettos is also a show about facing uncertainty and growing up. For Jason, it’s a literal coming of age coupled with the upheaval of adolescence. For his father, it’s a different journey toward maturity, taking responsibility for his actions, and navigating the precarity of Whizzer’s health. The context of the AIDS epidemic also holds weight around mortality and maturity. In the beginning of the epidemic, the majority of patients were young, previously healthy gay men. Individuals in their 20s, 30s, and 40s were suddenly facing death and dying in ways that were not normal for their age group. Patients were presenting with opportunistic infections previously seen primarily in weak and elderly people. Firsthand accounts talk about the strangeness of preparing for your own death at a young age, and the shock and devastation of visiting hospitalized friends so sick that they physically resembled much older men—their bodies prematurely aging and in many cases, ultimately failing. This first generation impacted by AIDS was one for whom time accelerated. Prompted to grow up quickly as the difficulties of late-life came early, they were saddled with experiences beyond their years, like caring for terminally ill friends and lovers, watching them die, and attending funerals on a weekly basis.

While the argument above deals with the knowledge gap between characters and audiences in the performance of aging texts, there is another significant knowledge gap that bears discussion. Falsettos is an innately Jewish show—and it’s Jewish at its heart in a key way that goes beyond the many direct references in the text. One of Judaism’s core values is bikur cholim, Hebrew for “visiting the sick”—a mitzvah, or obligatory Jewish commandment, as well as an act of gemilut hasadim (loving kindness), a foundational social value in Jewish teaching. The obligation of bikur cholim is not simply to visit those who are ailing, but to care for them, look after them, and help alleviate their suffering. In modern times, it’s seen as having a more general spiritual effect: decreasing loneliness, providing a listening ear, or a hopeful, cheerful presence.

Jewish tradition also asserts a need to acknowledge and name suffering and sickness, and the importance of bearing witness to loss. It holds that potentially unsettling passages in the Torah—including several chapters entirely focused on graphically detailing illness—must not be skipped, but rather chanted aloud, discussed, and grappled with. Jewish mourning rituals center on acknowledging loss before healing can begin. You would think, then, that even despite not knowing how or why these people were sick (a knowledge gap of a different sort, but a knowledge gap all the same) the Jewish community would not turn away.

However, despite liturgy around treating the ostracized and suffering with dignity, historians have found no evidence of an organized American Jewish response in the earliest—and perhaps most difficult—years of the AIDS epidemic. Most Jewish leaders were silent—some rabbis refused to lead burial rituals for AIDS victims and obstructed AIDS education and activism. Synagogues in individual communities generally did not respond to the crisis unless they were specifically gay synagogues, which had begun forming in the 1970s and acted as local beacons of support.

The first initiative on a widespread organizational level did not come until 1985—over four years into the epidemic. A gay and lesbian synagogue in San Francisco (the same synagogue where, on Yom Kippur that September, a gay rabbi had delivered one of the first two documented Jewish sermons to mention AIDS) successfully lobbied for the Reform Jewish movement to adopt a resolution on AIDS. It called for funding, resources, and prohibition of discrimination against people with AIDS and their families, and resulted in the creation of the Union of American Hebrew Congregation’s Committee on AIDS. Additional initiatives across Jewish movements followed, more broadly aligning action with the values of bikur cholim and gemilut hasadim.

Contrasting this with what we see in Falsettos highlights the utter extraordinariness of what Jason does in the second act when he chooses to have his bar mitzvah in Whizzer’s hospital room. When a child becomes a b’nai mitzvah, it signals the start of their obligation as a Jewish adult to fulfill the commandments. Jason’s acceptance of Whizzer, illness and all, shows a deep connection to Jewish values—as does his decision to forego a lavish party in his honor to include a loved one who is ailing. Further, holding the event in the hospital—in a place where illness and mortality are inescapable —directly acknowledges suffering. By embracing these values as part of the very ritual of entering into Jewish adulthood, he meets the transition by facing discomfort head-on and showing care for someone whose condition would lead society to ostracize others like him—a show of enormous maturity. He grows up.