Faith, Logic, and Misunderstanding

In tennis, to score zero is to score “love.” There are two theories about the origin of this term. One is that it comes from an English mispronunciation of the French word for egg, l’oeuf. A score of 0, because of its ovular shape, is often referred to as a “duck egg” or “goose egg.” However, most understand this to be apocryphal – French tennis players don’t say l’oeuf when they fail to score. The other theory is that if you score a zero, you are not playing to win, but for the love of the game.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead opens on our titular characters betting on the toss of a coin. It keeps landing on heads in Rosencrantz’s favor: “Seventy-six–love,” he announces. Guildenstern, reflecting on his astonishing loss, responds: “A weaker man might be moved to re-examine his faith, if in nothing else at least in the law of probability.”

There’s no need for Guildenstern to lose faith. The law of probability isn’t being broken here. Any single sequence of heads and tails 76 times is a rare, yet probable, occurrence; in fact, any sequence of heads and tails 76 times has the same probability of occurring, thus a series of exclusively heads should be no more surprising than any other. When faced with a seemingly irrational series of events – be it the back and forth of the tennis ball or the statistical anomaly of a series of coin flips – we might think that turning to rational systems (scorekeeping and probability among others) to make sense of these events would give us a feeling of security.

However, Stoppard shows us that rational explanations can feel less believable than the irrational. We have less faith in them. In fact, when his characters provide rationales for seemingly impossible events, things tend to come to a crashing halt. Nonsense, silliness, and absurdity give them more to go on. Meaninglessness does not forestall action on Stoppard’s stage, but drives it. In other words, rather than accepting a score of 0 as the decisive conclusion of a tennis match, Stoppard prompts us to ask: What if you recast this zero as an egg, translate this egg into French, mistranslate it back to English, and somehow arrive at love?

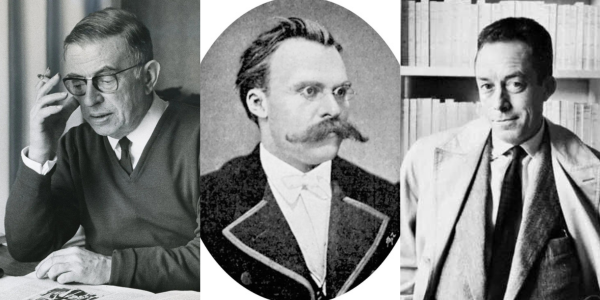

Stoppard, remarkably, turns existential paralysis into a motivation for action. He claims that he had no intention of exploring metaphysics in this play, and yet he confronts a question volleyed back and forth between many Western philosophers: What can one do in the face of meaninglessness? The existential philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre, would say that, once confronted with the destruction of religious faith in the wake of science and reason, we must make meaning for ourselves. If nihilism offers another response to meaninglessness, Frederich Nietszche warned us that the nihilistic impulse is a dangerously destructive one: the nihilist believes that if the world cannot exist as it should, the only solution is to dismantle the world as it is. And the absurdist, Albert Camus characterized absurdism as the acceptance of both the world’s fundamental irrationality and our necessity to make sense out of it anyway.

At various points, Stoppard’s characters act upon different impulses in the face of nothingness. They invent; they destroy; they question without expectation of an answer. While on their way to England, Rosencrantz asks: “So we’ve got a letter that explains everything?” Guildenstern confirms: “You’ve got it.” However, Rosencrantz misunderstands; he takes “it” to mean the letter rather than “the gist.” Panic ensues. “You seemed so sure it was you who hadn’t got it,” Guildenstern chides. “It was me who hadn’t got it!” Rosencrantz exclaims. Guildenstern then produces the letter from his own pocket. Rosencrantz, however, has forgotten why they were looking for it. “We thought it was lost,” Guildenstern explains.

This interaction ends just as it began: Guildenstern has the letter but “the gist” is still lost on them. The letter – the thing that should “explain everything” and provide rationale for the events of the play thus far – does not provide much in the way of understanding. Instead, it is the act of not “getting it” that gives the scene its momentum.

When watching Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, we don’t necessarily have to “get it.” It is not that the problems Stoppard’s characters face are impossible to understand – in fact, Stoppard often provides more than enough explanation to get at the logic behind a particular conundrum. Rather, understanding something does not give us much to do in its wake. It’s a dead end. We’ve found it’s far more fun (and perhaps more productive) to revel in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s misunderstandings than to resolve them.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead runs from March 29 – April 21, 2024. Tickets are available online or by calling the Box Office at (773) 753-4472.