Ecstatic Worship and the Pentecostal Experience

The Gospel at Colonus opens with a classic American art form: the sermon. Theseus, transformed from Sophocles’s ideal Athenian king to a Black Pentecostal pastor, delivers a damning account of the sins of now-disgraced Oedipus: he murdered his father, married his mother, and brought into the world children of incestuous parentage. Theseus’s sermon is framed by all the elements of a conventional Pentecostal service, from its stirring music to its rich language of hope and redemption.

Like the central figures of Gospel, Black Pentecostals have been preaching, dancing, singing, and sinning since Pentecostalism was conceived in the early 1900s. Indeed, the rich religious life-worlds of African Americans are at the heart of the denomination. It was William J. Seymour, an African preacher and the son of formerly enslaved parents, and Lucy Farrow, a formerly enslaved woman and the niece of Frederick Douglass, who were largely responsible for fanning the flames of Pentecostalism. Around 1905, Seymour and Farrow had been students of Charles Fox Parham, a white traveling evangelist who taught that people must break with the corrupt ways of the world in order to draw close to God and renew Christianity. Parham promised, drawing on the New Testament Book of Acts, that those who followed him would receive what he called “baptism in the Spirit,” an experience of contact with the Holy Spirit that produced overwhelming emotion and could result in radical gifts like the speaking of strange tongues (or glossolalia) and the power of divine healing.

Seymour and Farrow were early and enthusiastic converts of Parham, in spite of his segregationist politics. In 1905, Seymour traveled to Los Angeles to become a pastor at a small Holiness church. When the position fell through, he founded a new congregation and invited Farrow, who was said to be rich in gifts of the spirit, to join him. The church grew rapidly, and after only a few months it was forced to expand into a larger space—an old building that had once been a boarding house and a stable—on Azusa Street. While its members were primarily poor or workingclass African Americans, there were nonetheless people of “all ages, sex, colors, nationalities and previous conditions of servitude” in attendance at what came to be called the Azusa Street Revival.

Standing amongst the fallen lumber and crumbled plaster that littered the mission’s dirt floor, Seymour, Farrow, and hundreds (some even say thousands) of worshippers clapped, sang, and stomped themselves into a frenzy three times a day, seven days a week. Reports from revivalists proclaimed that the Holy Spirit had descended amongst them, giving them the power to speak in foreign tongues and heal broken bodies. By the summer of 1906, the services reportedly became so crowded that people were spilling out of the building and into the street. Those unable to gain entrance watched through windows in the hope that they might “catch the spirit,” or at least a story worth telling (or printing).

At the same time that the participants at the Azusa Street Revival were speaking in tongues and shouting their songs into the Los Angeles night, other Pentecostal missionaries were seeding their own revivals across the country and around the world. In Chicago, Black Pentecostal churches became a fixture of the city’s religious landscape, swelling with African Americans who had come to the city as part of the Great Migration. By 1919, there were over a hundred Pentecostal or Holiness storefront churches. More established churches like All Nations Pentecostal Church, led by Pastor Lucy Smith and a host of female “saints,” held a wildly popular Wednesday night healing service and hosted a radio broadcast from the 1920s through the 1940s, with thousands of primarily Black Chicagoans in attendance. In 1955, Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ presided over the funeral of Emmett Till, a Chicago child murdered by white supremacists while visiting his family in Mississippi. The church hosted some one hundred thousand mourners that September and is now understood to be a key site in the birth of the American Civil Rights Movement.

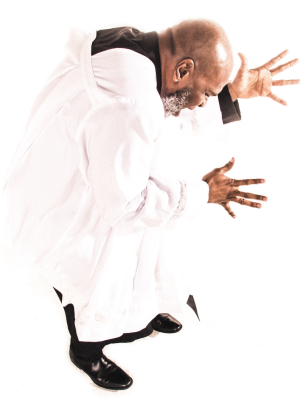

Many of Chicago’s Black Pentecostal churches embraced the ecstatic forms of worship popularized by Seymour, Farrow, and later revivalists, including exuberant dancing, shout bands, emphatic breath (also known as “whooping”), healing through the laying on of hands, and speaking in tongues. They also crafted their own forms or iterations of such practices, as the city’s various urban cultures shaped and were shaped by the denomination. First Church of Deliverance, whose choir reached national renown, was the first church to embrace the now-customary sound of the Hammond Organ, informing Black religious soundscapes for decades to come. The influence of the Hammond Organ can still be heard in Pentecostal churches today, and in the gospel music that tells Oedipus’s story in Gospel.

Pentecostalism is fundamentally about experience—the embodied, highly emotional experience of the Holy Spirit that goes beyond rational reflection or textual study (though these, too, are significant). It is, at its heart, about the senses—practitioners’ sensory experiences of God and the world through what their bodies can feel and know. Through The Gospel at Colonus, Court Theatre offers guests a window into that experience. It is a classic tale of sin, disgrace, and redemption told with and through a uniquely American idiom. There are few experiences like it.

Emily D. Crews is the Assistant Director of the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion at the University of Chicago. Her research and teaching investigate the ways that women’s religious lives are bound up with issues of race, gender, and reproduction. Her current research project focuses on the significance of alternative reproductive health practices to the construction of certain forms of white femininity in evangelical Christian communities in the American South. Dr. Crews is the co-editor of Remembering Jonathan Z. Smith: A Career and Its Consequence (with Russell McCutcheon, 2020) and African Diaspora Religions in 5 Minutes (with Curtis J. Evans, forthcoming 2023).