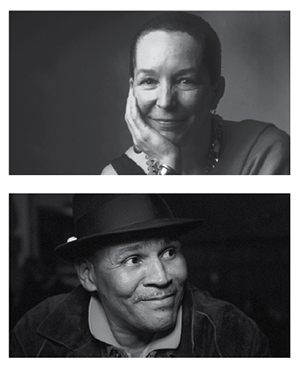

In Conversation with Playwright Pearl Cleage & Director Ron OJ Parson

Best-selling novels, plays, and poetry—Pearl Cleage has written it all. Her 1995 play Blues for an Alabama Sky thrusts audiences into the creative ferment of the Harlem Renaissance, just as the problems of the Great Depression begin to overshadow artistic triumphs and creep into characters lives. While set in the past, her work sends echoes to us in the present that are impossible to ignore. Court staff member Shelby Krick enjoyed a fascinating conversation with Cleage and Resident Artist and Director Ron OJ Parson.

In Blues for an Alabama Sky, you’re not writing about the Harlem Renaissance alone. You also focus on the Great Depression. How do you find that this time period intersects with the Great Depression, and why was that an inspiration for your work?

In Blues for an Alabama Sky, you’re not writing about the Harlem Renaissance alone. You also focus on the Great Depression. How do you find that this time period intersects with the Great Depression, and why was that an inspiration for your work?

Cleage: When I set Blues in the middle of the Harlem Renaissance, I realized we always write about it as a period of wonderful creative energy … people were in an opportunistic moment making great work. But once the stock market crashed, a lot of that money dried up and lots of artists were in worse times—especially black artists. I was more interested in placing a story, I realized, in that time when a lot of that hope and artistry has dried up, and how different people reacted to it. Angel responds with absolute fear. Guy’s response is to pursue a moment beyond the present, and to become a citizen of the world.

Being a citizen of the world, having hope past that moment—I think these thoughts resonate with our audience given what’s happening in our country right now. Have things changed, or do we still have the same historical motives?

Cleage: Absolutely. Running through African American history and literature, there have always been two responses. One is that “we’re here, we belong here, and we’re not going to be run off.” The other is that “we don’t really belong here, and we don’t really like it here.” [The latter] becomes the impetus to leave, to go to West Africa or Paris and become a citizen of somewhere else. My father was a Black nationalist, and his attitude was always that we’re going to dig in right here. But I was always fascinated by Langston Hughes and the ex-patriots; what would happen if we left and tried something new? Doc and Delia represent people like my dad. They’re here in Harlem, they have gifts that could take them out of the realm of a poor struggling community. Their class and privilege doesn’t drive them to leave.

Parson: I’ve always loved the whole environment of the Harlem Renaissance, the richness of it, and it’s always an honor working on your pieces, Pearl. When people walk into the theatre, I want older people to say, “That looks like my grandmother’s house!” Even before the play starts, they have the feeling of going back to that time. The timing is so right for some of the classic plays, because they’re more relevant now than ever.

Cleage: Yes, it’s interesting. We just did a 20th anniversary production [of Blues] at the Alliance Theatre, and I hadn’t seen the play for a long time. Beforehand, I thought, do I want to see this play again? Is it necessary to do it? Then I said to myself—wow! Intolerance, homophobia, anti-abortion … I could be writing this right now.

Parson: I was asked to do this during [the aftermath of] Ferguson, and I read it and said, this is today. I can do this and make this relevant to people who may think that this was just the past. We want artists to create artwork for the set that connects the show to the community. When they come, they see that there is a fire here that instills something new.

Talk to us about your original ending, which will be produced here at Court. What does this change do for your story, and why include it now?

Cleage: When we first did [Blues] at the Alliance, we couldn’t keep my original ending, and so the new ending became the published one, lacking an extra character. The original ending was produced for the first time at the Alliance in the 20th anniversary production in 2015. The point of Angel is that she didn’t change, she didn’t learn the lesson, she isn’t redeemed. But I’ve seen so many productions where she is. That is not who this woman is. The original ending makes it much clearer and takes away the ambiguity.

Parson: I’m interested in her protracted struggle: that she’s going to make it work, make it happen, and she has her way to do that. She knows what she’s got to do to survive. When I was reading it I thought of Dutchman and how when she comes back, it’s the same cycle over again.

Cleage: It’s exactly that! I’ve been thinking even more now than when I first wrote it, people don’t change. They do what they do. We like to think that they would, but they don’t. Angel is always going to have that fear, that selfishness—she was always in it to do the best for her, to find a man who could protect her.

Parson: A good friend and mentor of mine, Steven Henderson, taught me that characters’ history before they get on stage and on the page is so important. It’s how they got to where they are before people see them, and that’s a whole world. I like to get into that with all of these characters because that depth is there for me: it’s in the art on the walls, on the carpet.

Bringing plays from the African American canon to life on Court Theatre’s stage is a crucial part of our mission. For you personally, why is it so important to keep producing these classic works?

Cleage: When young people think of this time, it’s so far removed and dusty. So I didn’t want to write biographical work that’s about real people. But somebody knew these real people and went to their parties. Part of the pleasure is having these characters move around in this world of real people, so you can recognize it or learn from it.

Parson: I’ve been working in Chicago for 20 years, so it’s good to have young, fresh actors. But it’s interesting to learn that in training programs, they do Shakespeare and other classics, but they don’t know the work of the Harlem Renaissance or the Civil Rights movement. As actors of color, we need to do this stuff.

Cleage: When I was 11, I saw A Raisin in the Sun. The auditorium was packed with an all black audience, all black community. When the show ended, there was a beat of absolute silence, then everyone stood up and clapped for 15 minutes! That was when I realized: poems are great, novels are good, but I want to be a playwright.

We’re in a time when art is certainly more important than ever. What inspires you to keep working and moving forward?

Cleage: I can’t imagine not writing. I’ve always felt that my writing is a vehicle to tell the truth, allow audiences to see life, and to be a part of the resistance. It couldn’t be more important now to write about compassion, put forth the truth, and question what is the longing.

This is not the first time we’ve had to deal with an adversarial relationship with the government; I remember when segregation was legal. We continue to move forward. We’ve always done theatre because we’re determined to. I never think about stopping; I always tell myself to sit down and write everything I know! We can find a moment when information from the past can be transmitted to the youth now. We must find them where they are, and meet them with the highest possible level of what we do.