The Genesis of All My Sons

Arthur Miller’s directions for writing a good play were simple. “The best model,” he said, “is the Book of Genesis. You read about the Creation, and in only a page and a half, you’ve got the human race. That is the way to tell a story, a story that never dies. Less is better. Why? Nothing is wasted. It all counts.” In 1943, when he began to write All My Sons, Miller was 28 years old. He dreamed of creating a play that would distill the trauma and tragedy of World War II into one day in the life of an American family. Turning to the Old Testament for inspiration made sense to him: the unfolding global conflict was Biblical in its destruction.

Arthur Miller’s directions for writing a good play were simple. “The best model,” he said, “is the Book of Genesis. You read about the Creation, and in only a page and a half, you’ve got the human race. That is the way to tell a story, a story that never dies. Less is better. Why? Nothing is wasted. It all counts.” In 1943, when he began to write All My Sons, Miller was 28 years old. He dreamed of creating a play that would distill the trauma and tragedy of World War II into one day in the life of an American family. Turning to the Old Testament for inspiration made sense to him: the unfolding global conflict was Biblical in its destruction.

As one historian has written, World War II was “the largest event in human history—the greatest and most terrible of all human experiences.” From September 1939 to August 1945, people around the world were shaken from the normal round of everyday life into violence, catastrophe, chaos and devastation. More than 60 million died. Those who survived often found it difficult to talk about their experiences: what had happened to them, in many cases, defied comprehension.

Arthur Miller was a non-combatant. Classified 4-F because of a high school football injury to his knee, he stayed behind while his beloved older brother, Kermit, enlisted as an Army infantry captain and embarked for Europe. Throughout the war, Kermit would write searing letters home to “Arty” from the battlefields of France and Belgium, filled with stories about the self-sacrifice, brotherhood and devotion of the young men he led “into the line.”

Miller had studied playwriting in college; the work he found to do during the war drew on that skill. From 1942 to 1945, he was a roving reporter, visiting Army hospitals and training camps, talking to soldiers and turning their stories into patriotic radio plays for CBS and NBC. For one broadcast, Miller interviewed Air Force pilots whose planes had been shot up over Germany, and who now were hospitalized stateside. The horrific injuries sustained by the men—many of them no more than 19 or 20 years old—“moved me terribly,” Miller said. “They were all younger than me, and marred for life. I couldn’t turn my back on them and I felt I owed it to them to write their stories.”

The genesis of All My Sons came in 1943, Miller said, when he was feeling like “a stretched string waiting to be plucked—a young, fit man barred from a war others were dying in.” The chord of inspiration struck when he read “about a young girl somewhere in central Ohio who turned her father in to the FBI for having manufactured faulty aircraft parts.” The scandal dominated the news: a profit-minded industrialist at the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Corporation knowingly shipped defective engines to the U.S. Army Air Forces, causing the deaths of 21 pilots who flew P-40 Warhawk fighter planes.

This was the plot Miller had been waiting for, a story about a child’s powerful sense of social responsibility triumphing over her loyalty to her own father. For Miller, the anecdote distilled the question at the heart of the war effort: Was our struggle only for our own families, or were we fighting for the family of all humankind?

To trace the development of All My Sons in the playwright’s imagination, we turned to the Arthur Miller Collection at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas, Austin, where Miller’s journals, diaries, correspondence and wartime radio scripts are archived, along with the early drafts of All My Sons.

We read the diary that Miller kept from 1943 to 1945, a volume filled with poems and scene fragments, and his thoughts about how this play might transform the hearts and minds of American audiences. Miller believed “writing a worthy play” was comparable “to saving a life—it was one of the most important things a human being could do.” He hoped this piece of theatre would change the world.

We compared Miller’s early drafts of All My Sons—two unfinished plays titled “The Sign of the Archer,” and “Morning, Noon and Night”—to the completed version. Studying these early iterations of the work allowed us to dive beneath the surface of the finished text and explore how the characters, story and language took shape in Miller’s mind.

Miller maintained that in this play, “I sought to reconstruct my own life, becoming my brother from time to time, my father, my mother, putting on their forms and faces.” When we learned the playwright modeled Kate, Joe, and Chris Keller on his own family, we researched the Millers carefully, so as to invest the Kellers with identities rooted in fact.

Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, the Millers had achieved extraordinary success as garment manufacturers in the decade after World War I, only to lose everything in the Crash. Miller witnessed his parents’ swift plummet from wealth to poverty in 1929. He watched his brother, Kermit, go to war in 1942 and welcomed him home again in 1945, broken and shell-shocked, a shadow of the man he once had been.

By transferring the weight of his own personal history onto a day in the life of an average American family, Miller infused All My Sons with the full power of the defining events of the 20th century: the immigrant experience, the Great Depression, World War II, the coming of peace, and the soldiers’ return.

All My Sons is a story of creation and destruction, the revelation of a playwright who believed building a better world was the only answer to the global ordeal of war. ■

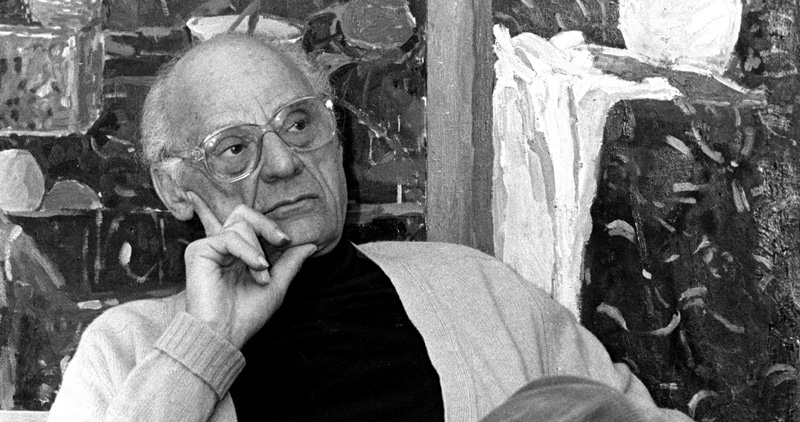

Photo: Playwright Arthur Miller pictured during an interview in his apartment in New York, 1987. Miller said that—after coming out of depression, trying in a dozen ways to stir the country’s soul, and being hauled before Congress for being un-American—he “has survived, and that’s not bad.” (REUTERS/Mark Petersen MP/PN)