No More Precious Stones

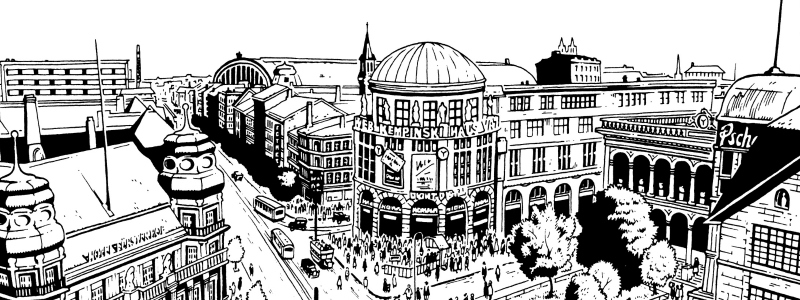

The Weimar Republic often appears in the popular imagination as a cultural object. It is the snapshots of urban decadence in Christopher Isherwood’s 1939 novel, Goodbye to Berlin; it is the brassy tunes of Bob Fosse’s 1972 musical based on that novel, Cabaret. It is the feverish choreography of the hit television series, Babylon Berlin. It is the cacophonous ink drawings of Jason Lutes’ graphic novel, Berlin, the dynamic adaptation by Mickle Maher, and the kinetic stagecraft of Charles Newell. We come away from these works with a vibrant aesthetic language to describe this complex time and place in history: Weimar is a kaleidoscope, a collage, a variety show, a dance on the edge of a volcano.

That Weimar lives on as a style, a sound, a beat is of course due to the extraordinary cultural energy of its capital city during the period. Berlin was a hub for jazz music, variety shows, cabaret, and opera. As Kid Hogan observes in the play, “There’s not a note of music in this city that’s not pushing against every note that came before.” It was also a city of “cinema, cinema über alles,” in the words of expressionist poet Hans Harbeck, home to the country’s largest film production company, UFA, which brought icons of avant-garde cinema to national and international audiences, such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis. In the field of the visual arts, Berlin was a seat of the Dada movement; the founding place of the expressionist November Group; an epicenter of the New Objectivity movement. As the city grew, it became a platform for bold experiments in architectural innovation, particularly in the field of public housing: the sprawling expressionist estates designed by Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius, Martin Wagner, and Hans Scharoun still assert themselves in the city’s urban landscape. The characterization of Berlin as “Chicago on the Spree,” once meant as an insult, became during the 1920s a badge of the city’s exhilarating modernism.

One of the challenges of understanding the history of Weimar has been reconciling its avantgarde cultural foment with the rise of National Socialism. The era of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil, of the Bauhaus and Dada was also an era of extreme reactionary conservatism and fascism. Some historians have addressed this problem by reminding us that even if Berlin has become the iconic symbol of Weimar, the city is hardly representative of the political or cultural realities of the rest of Germany after the devastation of the First World War. Others have pointed out the ways in which both National Socialism and Weimar’s artistic renaissance were both products of a reigning spirit of experimentation oriented towards the discovery of radical new ways of conceiving individual and collective life. Others have posited that the energy of Weimar culture drew in many ways from its position outside of the mainstream. The true home of Weimar’s spirit, the historian Peter Gay writes, was, tragically, in exile.

Berlin confronts this period of simultaneous creativity and crisis by bringing us eye to eye with its consequences on the ground. Amidst the maelstrom of sound and image unfolding on the stage, we encounter the deep uncertainty of the story’s central characters about whether their writing, drawing, musicking can meet, or even contain, the catastrophes quickly unfolding in Weimar’s final years. Perhaps, as the character Kurt Severing proclaims early in the piece, “In Berlin, fine art and revolutionary politics are joined at the hip.” The character Anna is not so sure: “Maybe art is only calling us to art,” she confides to Marthe. “Art can say nothing matter of fact about reality.” Marthe embraces drawing, but for its ordinariness, rather than for its world-changing potential. By capturing this complex convergence of aesthetic exuberance and aesthetic doubt, Berlin delivers us a powerful rendering of Weimar as a work of theater, informed by the period’s anxiety about the relationship between culture and life. In the words of the playwright Friedrich Wolf, writing in 1929: “We do not want any artworks, even if they are precious stones. We want the truth of our time.”

Join us in Berlin and don’t miss this exhilarating world premiere, onstage from April 19 – May 11, 2025. Tickets are available online or by calling the Box Office at (773) 753-4472.

ALICE GOFF is Assistant Professor of German History and the College. Her research and writing focus on cultural and intellectual life in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She is the author of The God Behind the Marble: The Fate of Art in the German Aesthetic State (University of Chicago Press, 2024). Goff recieved her PhD in history from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2015. From 2015 to 2017, she was a postdoctoral fellow in the University of Michigan’s Society of Fellows in the departments of History and Germanic Languages and Literatures. Before beginning graduate work in history, Goff completed a master’s degree in archives and records management and a certificate in museum studies, and she maintains an active interest in contemporary archival and curatorial practice.