On Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun

When Sidney Poitier escorted 29-year-old Lorraine Hansberry to the stage in response to calls of “Author! Author!” from an enthusiastic audience that had just witnessed the 1959 Broadway opening of A Raisin in the Sun, the young playwright was as yet uncertain which play her admirers were applauding. Had they been mesmerized by a story that appeared to affirm the vitality of the American dream of homeownership by dramatizing the injustice of the racism that denied many Black Americans access to that dream? Beguiled by a play that, despite compelling portrayals of three complex Black women, had made the redemption of its major male figure the goal of its plot resolution? Perhaps captivated by a vision of race group pride and identity eclipsing a pursuit of mere material prosperity? Or maybe charmed by a well-crafted play about an American family, who happened to be Black, navigating their version of the challenges facing most mid-20th-century Americans?

Judging from the myriad responses to A Raisin in the Sun immediately upon its production and across decades of revivals, film adaptations, and scholarly studies, the power of Hansberry’s drama—which was awarded the 1959 New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play, beating out plays by such luminaries as Archibald MacLeish, Eugene O’Neill, and Tennessee Williams—may have been its capacity to sustain a variety of not-quite-compatible interpretations and the way it reflected the kaleidoscopic reality of its author, whose 34 short years of life tumbled her into many of the momentous social and political changes that defined American life at the middle of the twentieth century.

When Hansberry was born in Chicago in 1930, seven months after the Stock Market crash that ushered in the Great Depression, Black Americans, like their fellow citizens, were vigorously debating the paths the nation might take towards becoming a just society. Some argued for what political scientist Preston E. Smith II has called “racial democracy”—the idea that justice and fairness merely demanded that Black Americans, and members of all other racial groups, not be discriminated against in their pursuit of happiness and prosperity within a liberal capitalist America. Hansberry’s parents largely held this view. Her father, Carl, was a real estate speculator who at the time of her birth owned property valued up to $250,000 (more than $4 million in today’s economy), and her mother, Nannie, was serving as a Republican Ward committeewoman. Together, as foes of racial discrimination, they established the Hansberry Foundation “with a $10,000 endowment to support legal remedies to racial discrimination.” Even more consequentially, Carl Hansberry was named the respondent in a legal case alleging that he had illegally purchased a property covered by a “restrictive covenant,” the term for discriminatory contracts that were the norm in Chicago and elsewhere, through which “white homeowners and real estate developers and agents” agreed not “to sell lease, or rent to racial and religious minorities for a specified period of time unless all signers agreed with the transaction.”1 The ensuing legal battle went all the way to the US Supreme Court as Hansberry v. Lee (1940), where Hansberry prevailed in a ruling that signaled the beginning of the end of that form of discrimination.

“When Hansberry was born in Chicago in 1930, seven months after the Stock Market crash that ushered in the Great Depression, Black Americans, like their fellow citizens, were vigorously debating the paths the nation might take towards becoming a just society.”

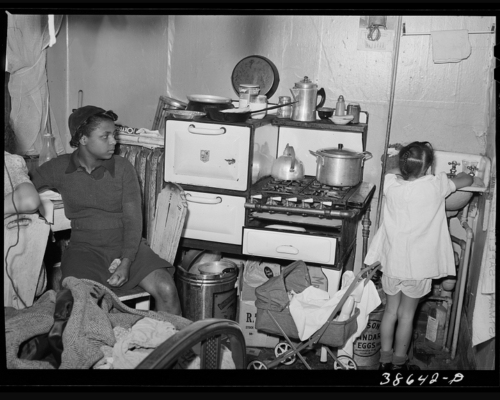

But Hansberry’s victory was only a partial one for most poor and working-class Black Americans seeking decent housing. As a real estate speculator, Hansberry had aggressively expanded the availability of “kitchenette” apartments—small units created by subdividing buildings so that seven or eight families were squeezed into a space that had previously accommodated one or two. Carl’s industrious conversions earned him the moniker, “the King of the Kitchenettes” while producing considerable wealth for him and his family.22 And while the apartments he rented to poor Black migrants may have been better than nothing, they were unheated, sometimes no larger than 100 square feet, and forced renters to share a bathroom with all of the other units on that floor. Kitchenette living was oppressive, and its deprivations provided the bleak cockroach- and rat-infested settings for Richard Wright’s Native Son, Gwendolyn Brooks’s Maud Martha, and of course, Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun.

Although she never repudiated her family’s commitment to real estate, Lorraine was not, politically, her parents’ child. Against their commitment to racial democracy, she came to embrace ideas closer to what Smith calls “social democracy, the belief that attacked class stratification and held ‘that citizens should have access to decent housing regardless of their ability to pay for it.’”33 As a 17-year-old at the University of Wisconsin-Madison—where she attended meetings of the Labor Youth League, a socialist organization—Hansberry saw a production of the socialist Irish playwright Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, which left her “in a transcendent mood” and set her on the course of becoming a playwright herself.44 In 1948, she supported Henry A. Wallace’s Progressive Party campaign for president of the United States. By the 1950s in Harlem, she was openly espousing Marxist ideals and worked for a time at the newspaper, Freedom, which had been founded by Paul Robeson after his passport had been suspended following his refusal to affirm that he was not a Communist Party Member. While in Harlem, Hansberry also met and married Robert Nemiroff, a Communist Party fellow traveler, and took a course on Marxism and anticolonialism with W.E.B. Du Bois.

All of these influences and experiences would exert their force when Hansberry came to write A Raisin in the Sun, which takes its title from Langston Hughes’s short, evocative poem “Harlem,” from his 1951 Montage of a Dream Deferred. The play unfolds in a shabby but not scandalous kitchenette, where the overcrowded Younger family await the arrival of a $10,000 insurance settlement check after the death of the family patriarch, Big Walter. The windfall offers the possibility of changing the family’s fortune, but the competing visions of the family members put them in conflict with one another. Big Walter’s widow, Lena (Mama) Younger, sees the check as an opportunity to move to a home with a yard and a garden where her grandson, Travis, will be able to grow up away from South Side deprivation; a place where the tensions within her family may dissipate when they no longer have to live virtually on top of one another. That finding such a home will mean moving into what has been a whites-only neighborhood adds a significant complication to Lena’s dream. Her son, Walter Lee Younger, who lives in the apartment with his wife, Ruth, and their son Travis, dreams of leaving behind his job as a chauffeur by entering into a partnership to buy a liquor store as the first step to becoming a wealthy businessman. At odds with his vision is his sister. Beneatha’s aspiration is to go to medical school and to sort out her relationship with two different suitors, the Nigerian student, Joseph Asagai, who is committed to the struggle for African liberation, and another student, the stylish George Murchison, a scion of real estate-owning family not unlike Hansberry’s own.

Although Hansberry may have wanted Raisin to express powerfully her socialist political sentiments, her empathetic portrayals of the Youngers and their neighbors and friends, resulted in drama that flummoxed some of her politically-minded critics and reviewers. Indeed, in a recent assessment of the play, University of Chicago Professor Adrienne Brown has argued that Hansberry’s play represents her “attempt to understand the complexities of feelings for and about property and its capacity to serve as both tether and tinder for [Black] visions of liberation.” In Brown’s view, it is George Murchison, “the queer progeny of a black property mogul” who despite his relatively minor role in Raisin, comes closest to embodying Hansberry’s pragmatic concession to the unavoidability of property acquisition as a way of advancing any progressive social vision at all.55

The history of American theatre might have unfolded quite differently had Raisin been the first play in a lengthy career for Hansberry, but fate had other ends in view. Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer in 1965 on the same night her second Broadway play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window closed at the Longacre Theatre after 101 performances.

KENNETH WARREN is the Department Chair and Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor in the University of Chicago’s English Department. His scholarship and teaching focus on American and African American literature from the late nineteenth century through the twenty-first century. His single-authored books include What Was African American Literature? (Harvard 2010), So Black and Blue: Ralph Ellison and the Occasion of Criticism (Chicago, 2003), and Black and White Strangers: Race and American Literary Realism (Chicago, 1993). He also edited Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle for The Norton Library (2023).

- Preston H. Smith II, Racial Democracy and the Black Metropolis: Housing Policy in Postwar Chicago (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2012) 194. ↩︎

- Charles J. Shields, Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind A Raisin in the Sun (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2022), 15. ↩︎

- Smith, xiii. ↩︎

- Shields, 72. ↩︎

- Adrienne Brown, The Residential is Racial: A Perceptual History of Mass Homeownership (Stanford; Stanford University Press, 2024), 243. ↩︎