Honoring Legacy

Director of Engagement Kamilah Rashied recently met with Raquel Flores-Clemons, archivist and head of the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection at the Woodson Regional Library, to discuss the necessity of preservation, a key theme of both Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution and the Black Power Series.

Intended to complement Stokely, the Black Power Series explores the monumentality of Black contributions to American history. Below, Kamilah and Raquel invite us to consider the role of information and community in the history of Black Chicago, setting the stage for the Black Power Series and—ultimately—Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution.

Kamilah: Can you tell us about your role and the Woodson Regional Library?

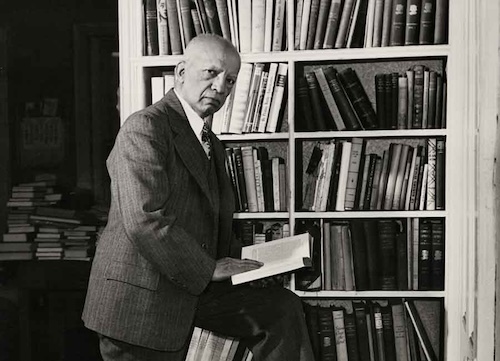

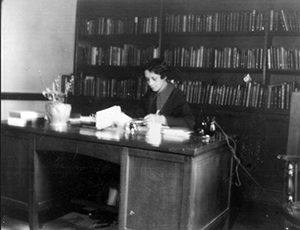

Raquel: I am an archivist, a librarian, and I currently serve as the head of the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, the largest collection of African-American history and literature in the Midwest and the second-largest of its kind in the nation in a public library setting. We have over 4,000 linear feet of archival materials, including documents and ephemeral material. In 1932, Vivian Harsh, Chicago Public Library’s first Black library director, opened the George Cleveland Hall Branch in Bronzeville—the first library in CPL to serve a predominantly Black population—and she started the Collection. Vivian Harsh and her staff developed programming that supported intellectual engagement, economic development, and provided a varied set of resources to the community. When Vivian Harsh retired in 1958 and later passed away, the Collection remained at the Hall Branch, but it had started to fall into disrepair. The community understood its importance, so they advocated for it to be in better condition. When the Woodson Regional Branch was being built, it came here, which is fitting because Carter G. Woodson—the branch’s namesake and a University of Chicago alumnus, funnily enough—was a colleague of Vivian Harsh.

Kamilah: I think that’s such a smart, beautiful connection between the Collection and the Woodson Library. Vivian Harsh became a librarian for the Chicago Public Library system one hundred years ago, in 1924, and she started the Collection at the Hall Branch after becoming Chicago Public Library’s first Black Library Director in 1932, as you mentioned. So, almost one hundred years in, what does the Harsh Collection look like today?

Raquel: We were fortunate to receive a $2 million grant from Mellon for the Renaissance Project, which offers support as we process collections that don’t yet have full access privileges. We’re also doing some digitization work. Our collection is a good mixture of material from folks who are nationally recognized and folks who are significant to local Black history. As we get more of these collections in a state where they can be researched—and the door opens wider for folks to come in, produce scholarship, and produce artwork—we hope more creatives explore interesting ways to apply these materials and make it immediately relevant to the national dialogue. I was really excited when you asked us to participate in the Black Power Series and, by extension, Stokely. It’s really great to see the Collection being used and amplified in this way. We hope to continue that work and, as more archives are made available from the Collection, we’ll be able to see more and do more.

Kamilah: What does it mean for you to be the steward of almost one hundred years of Black history, and to make that available to Chicago and the world?

Raquel: I feel very privileged to be in this role. I’m the first woman since Vivian Harsh to lead this unit formally, and I just simply love us. I love Black people, so I’m very careful with the Collection. I always want it to be true to the wide array of experiences of the Black community. Collections are made in particular spaces in time, and the Harsh Collection was developed almost one hundred years ago. Things were very different then, so there are some limited narratives, and it’s worth noting that the geographical makeup of the city in the Collection isn’t very diverse, either. Black Chicago history is often told through a South Side lens, but I’m from the West Side, so I definitely came in like, “Where we at?” When I’m able to intentionally grow the Collection, I look for those histories that tell a more inclusive story of the Black experience in Chicago. I became an archivist specifically to amplify and preserve Black history and culture in Chicago, because that’s the journey and experience that I know. That’s where I’m from. And this is a part of the fabric of American history. I feel very lucky that I get paid for something that I really, really enjoy doing.

Kamilah: Black people need to see their history, they need to know where they come from, and they need to have access to these resources. But also, all Americans need to see Black history and have access to these resources. Everyone needs to know what the Black experience has been, and I feel like archival ephemera is level one. It’s so material. It is literally what happened.

Raquel: You’re never going to get the full picture of history. You just can’t—there are too many people involved, no matter what—but archives bring you closer to a more accurate history. These stories belong to the community, so it’s really important to let people know that this is their space, too. As much as we love researchers who produce scholarly work, I’m excited when I see community members—small business owners, entrepreneurs, or even parents with kids—use the material for their personal journeys. They’re part of the legacy of what inspired Vivian Harsh. For her, it was really about the community. She wasn’t only invested in introducing new information about the community to itself; she also wanted to help folks live day-to-day and build a better quality of life.

Kamilah: That’s the difference between having this information in a public library rather than a museum. Anybody can make a reservation, explore the list of what’s in the Collection, and ask for those things to be pulled so that they can at engage them. Here, nothing’s ever out of circulation. And now, thanks to that funding you mentioned, you all have more resources to continue digitizing things so that people have even more access. That’s why I admire Vivian Harsh so much. It was revolutionary for her to say, “Information is powerful, and I want to preserve our culture—for practical reasons, for historical reasons, for spiritual and cultural reasons—and I want to put that in a space open to anyone.” That’s such a beautiful legacy project.

Raquel: Collections are only useful if they’re being used. Folks like you who are interested in the Collection are why it’s still here. We’re really excited to partner with you on this project.

We invite you to join us for the Black Power Series, from May 23 – June 10. All events in the Black Power Series are free and open to the public.

Raquel Flores-Clemons is Head of the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection at the Woodson Regional Branch of the Chicago Public Library. In this role, she also serves as Vice-Chairperson for the Black Metropolis Research Consortium (BMRC). An advocate for equity and access, Raquel maintains a deep commitment to capturing historical narratives of communities of color and engages hip-hop as a method of archival praxis. Raquel is passionate about connecting community members and organizers to valuable primary resources and is intentional in ensuring that historical gaps are filled by documenting and amplifying the often underrepresented historical narratives and contributions of BIPOC communities to better support efforts to create a more equitable society.